Fieldwork from a distance II

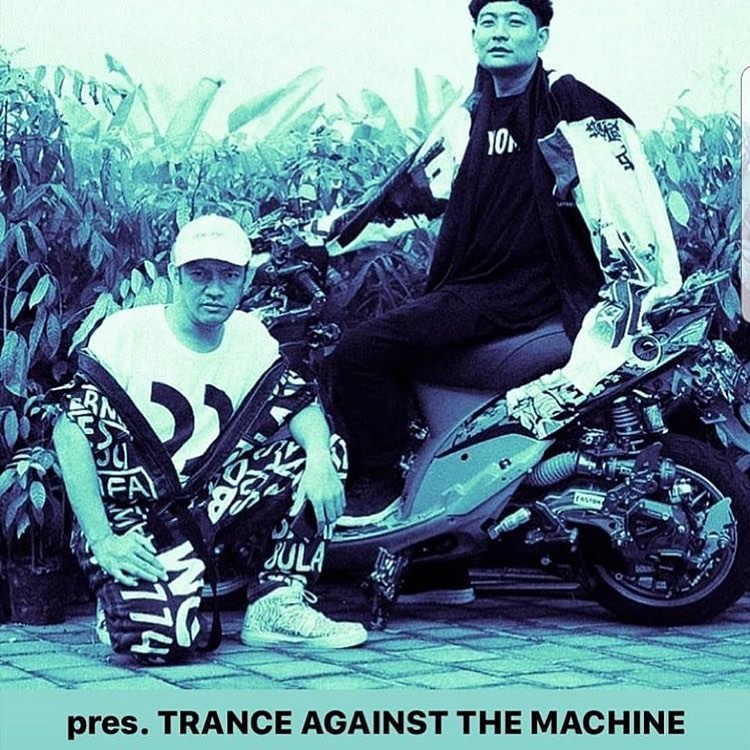

The catchy title “Trance Against the Machine” came to us via Instagram from Gabber Modus Operandi. The catchy phrase was accompanied by the following equally catchy image of the two protagonists of GMO, Kasimyn och Ican Harem:

An instant meme, the image and catch phrase publicised the 2019 global tour of GMO that also took them to the performance venue “Inkonst” in Malmö, Sweden, where we had the great fortune of meeting them again. As with everything GMO does, this meme is punk philosophy in action, provocative and thought-provoking at the same time. Take the motorbike in the image. The motorbike, often generically referred to a “Honda” in Indonesian, is a key fixture on the Indonesian noise scene: it is instrument as much as it is a symbol of protest and identity. It is a machine of protest. Every cog and every decibel of its unmuffled exhaust part of an aesthetic of rage against the corporate and state machine. A small machine of the common person to rage against the big machine. The Honda is a quintessentially Indonesian symbol and mode of transport of the “common person”. It is is also the main source of income for the Ojek driver, – motorbike taxis driven by school teachers, students and other to make an extra rupiah. Ojek drivers are however also a “proletariat-for-hire”, mobile protesters that can be bought by agents of the “big machine” to create the impression of popular support and/or outrage. In that sense, the motorbike is a small machine readily for hire to the big machine.

GMO always makes us wonder, makes us alert to things we had not seen before. GMO pushes us to rethink our central research questions in Java-Futurism: How, for instance, do we understand the specificities of an Indonesian noise and experimental music scene that so effortlessly connects to the memes and themes of the scenes of electronic musician Europe and the US? GMOs replacement of “rage” with “trance” opens up this question for us. With an obvious echo of (and respectful nod towards) the 1990s US “rap metal” band Rage Against the Machine, GMOs meme “trance against the machine” opens to the multiple and diverse paths we are exploring with this project. It seems to us that the ambivalence at the heart of the word “trance” – a Western dance genre as well as a Javanese ritual practice – is one that GMO want to maintain rather than resolve. We hope to do the same. We are therefore developing an article on “trance-music” (in the widest sense), as an example of how Indonesian experimental music weaves in and out of cultures, genres, politics, and historical awarenesses. Our main point in this article is to identify – using GMO’s musical punk philosophy as an example – Javanese experimental music as a type of irreverent political aesthetic that is at once globally specific and culturally universal.

Barred from travelling during 2020, we conducted an online follow-up interview in June 2020 with Gabber Modus Operandi (us in Skagen, Denmark, Kas and Ican in Bali, Indonesia). Thank you, Kas and Ican, for sharing your thoughts with us!

Comments